On this page, you find an overview of how education in Finland is organised in practice, together with useful background on values, history and everyday school life.

Welcome to learn more about Finnish education!

Introduction to Finnish Basic Education

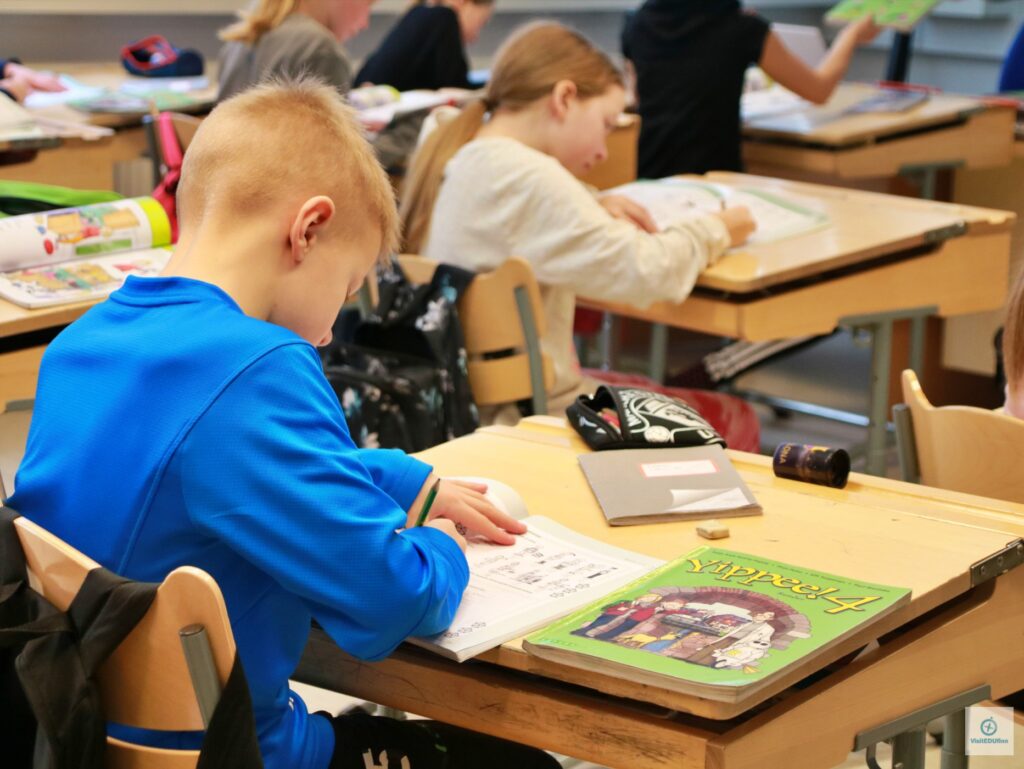

Finnish children start primary school the year they turn seven. The year before that is spent in pre-primary education (20 hours per week and 700 hours per year). Pre-primary education became compulsory in 2015 and is free of charge for families. It is part of early childhood education and can take place either in day-care centres or in primary schools.

Basic education begins at age seven and lasts for nine years. It is often described in two stages:

- Primary education, grades 1–6

- Lower secondary education, grades 7–9

Traditionally, these stages have been located in separate school buildings. However, it is now increasingly common to combine them into one comprehensive school, where pupils from age 7 to 15 study under the same roof.

After completing nine years of compulsory education, nearly all young people in Finland (around 95%) move on to upper secondary education, choosing either vocational education or a general upper secondary school.

The Finnish system is designed without dead ends. Learners can always continue their studies at a higher level of education. Because education is free of charge at all levels, higher education is accessible to all. Free education and flexible learning paths are seen as key conditions for lifelong learning, both for individuals and for Finnish society.

Equity – High-Quality Education for Every Child

Equity is a core value in Finnish education. Education is regarded as a basic right, and everyone is entitled to equal access to high-quality education and training.

Equity means that the potential of every child should be developed, regardless of:

- Gender

- Age

- Linguistic or cultural background

- Economic situation

- Place of residence

Basic education is non-selective:

- Schools do not select or stream pupils

- There are no gender-specific schools

- The whole age group attends the same comprehensive school for nine years

Pupils from different socioeconomic backgrounds learn together, which helps prevent social segregation.

The school network is geographically extensive, ensuring that pupils can attend a nearby school. Most children go to their local school, although it is possible to choose another school under certain conditions. Schools are not ranked, and “school shopping” is therefore rare in Finland.

The Roots of the Finnish Education System

Schooling in Finland originally developed in close connection with the church, as in many other countries. The Evangelical Lutheran Church, Finland’s national church, believed that everyone should be able to read the Bible in their own language. Already in the 17th century, the church began to teach people to read.

A national school system independent of the church was established in 1866, when public education began. Uno Cygnaeus, often called “the father of the Finnish public school”, played a central role. He advocated a system that would:

- Educate both boys and girls

- Be open to all social classes

- Include practical subjects in addition to academic ones

Public schools gradually expanded across the country, at first coexisting with church schools, especially in rural areas.

In 1921, compulsory education for all children aged 7–12 was introduced. This law was a major milestone for equity: every municipality had to provide schooling for all children, regardless of gender or socioeconomic background. However, the system still separated pupils into academic or civic tracks after four years of schooling together.

In the 1970s, basic education was reformed into its current form: a nine-year comprehensive school for all children. This reform combined the strengths of the older systems and balanced academic content with practical learning. The reform was implemented gradually: it began in Northern Lapland in 1972 and reached the Helsinki capital area by 1978. Since then, children from different social backgrounds have attended the same comprehensive schools throughout the country.

The school week has also changed. Pupils once attended school six days a week, but since 1971 weekends have been free. Today, the school year starts in mid-August and ends on the first Saturday of June, with 190 school days per year. There is a one-week autumn holiday, at least a ten-day Christmas holiday, and a one-week winter break. Overall, Finnish pupils spend comparatively little time at school among OECD countries, and school days are typically fairly short.

Quality of Education Guaranteed by Law

Basic education in Finland is regulated by the Basic Education Act (1998, with some sections revised in 2010). By law, every child in Finland is entitled to:

- Cooperation with parents – Schools and teachers are required to work together with parents and caregivers.

- A place in a nearby school – Municipalities must organise education so that travelling to and from school is as safe and short as possible.

- Safe school travel – If the distance to school is more than five kilometres or the journey is considered too demanding or dangerous given the pupil’s age or other circumstances, the pupil is entitled to free transport.

- A safe learning environment – Physical and emotional safety at school are both guaranteed.

- Guidance counselling – All pupils are entitled to guidance throughout basic education.

- Support for learning – Pupils have the right to remedial teaching, intensified support and special needs education whenever necessary.

- Encouraging assessment – The aim of assessment is to guide and encourage learning and to help pupils develop their ability to evaluate their own work.

- Balanced workload – Schoolwork, homework and travel to school must be organised so that pupils still have enough time for rest, free time and hobbies.

- Free welfare services – Pupils are entitled to the welfare services they need to participate in education.

Free Education at All Levels

Education in Finland is publicly funded at all levels, from pre-primary to higher education, and therefore free of charge for families. Free basic education covers:

- Instruction

- Learning materials and school equipment

- School meals

- Health care and dental care

- Pupil welfare services

If needed, it also includes transportation, special support and special needs education.

Local authorities (municipalities) provide most of the funding (around 75%), while the state covers the rest. State funding is not earmarked; municipalities decide how to allocate it. Key decisions in annual budgeting include teaching hours and group sizes, as these define the number of teachers required. Minimum teaching hours are set by law, but class sizes are not. In grades 1–6, teaching groups have on average about twenty pupils.

Most Finnish pupils attend public schools. Less than two percent of each age group study in state-subsidised private schools, which also follow the national core curriculum. Schools are not allowed to make a profit or charge tuition fees.

Free School Lunch Since 1948

One important element of Finnish basic education is free school lunch. In 1948, Finland became the first country in the world to serve a free school meal to every child. Early meals usually consisted of simple soups or porridges, and the goal was to support pupils’ health and give them enough energy for learning.

Today, school meals also serve a broader educational purpose. Food education is seen as a holistic pedagogical tool.

Each municipality must prepare a plan to support pupils’ welfare. This plan includes:

- Principles for arranging school meals

- Objectives for health and nutrition education

- Guidelines for teaching table manners

School meals help pupils learn about healthy diets and encourage them to eat more vegetables, fruit, berries, wholegrain bread, and low-fat milk. It is common for teachers to eat together with the pupils.

Children’s opinions are also considered. Schools may organise “children’s favourite food days” when pupils vote for their preferred dish. Feedback from pupils is used when planning annual school menus.

Curriculum as the Foundation – Learning for Life

The Finnish national core curriculum is revised roughly every ten years. The most recent comprehensive reform took place in 2014. At the heart of the renewed curriculum is the idea that every child should be supported to reach their full potential.

The national goals for education shape the entire curriculum. They focus on:

- Growth as a human being and active citizenship

- Essential knowledge and skills

- Equality, capability and lifelong learning

The renewed curriculum places strong emphasis on identity development. Every pupil has the right to succeed, and learning is seen as a way to build one’s identity, worldview and understanding of self, others and society.

Wellbeing and learning are viewed as inseparable. Schools support academic progress alongside personal growth, highlighting joy of learning and an active pupil role. The aim is to help children become curious, responsible and fair thinkers.

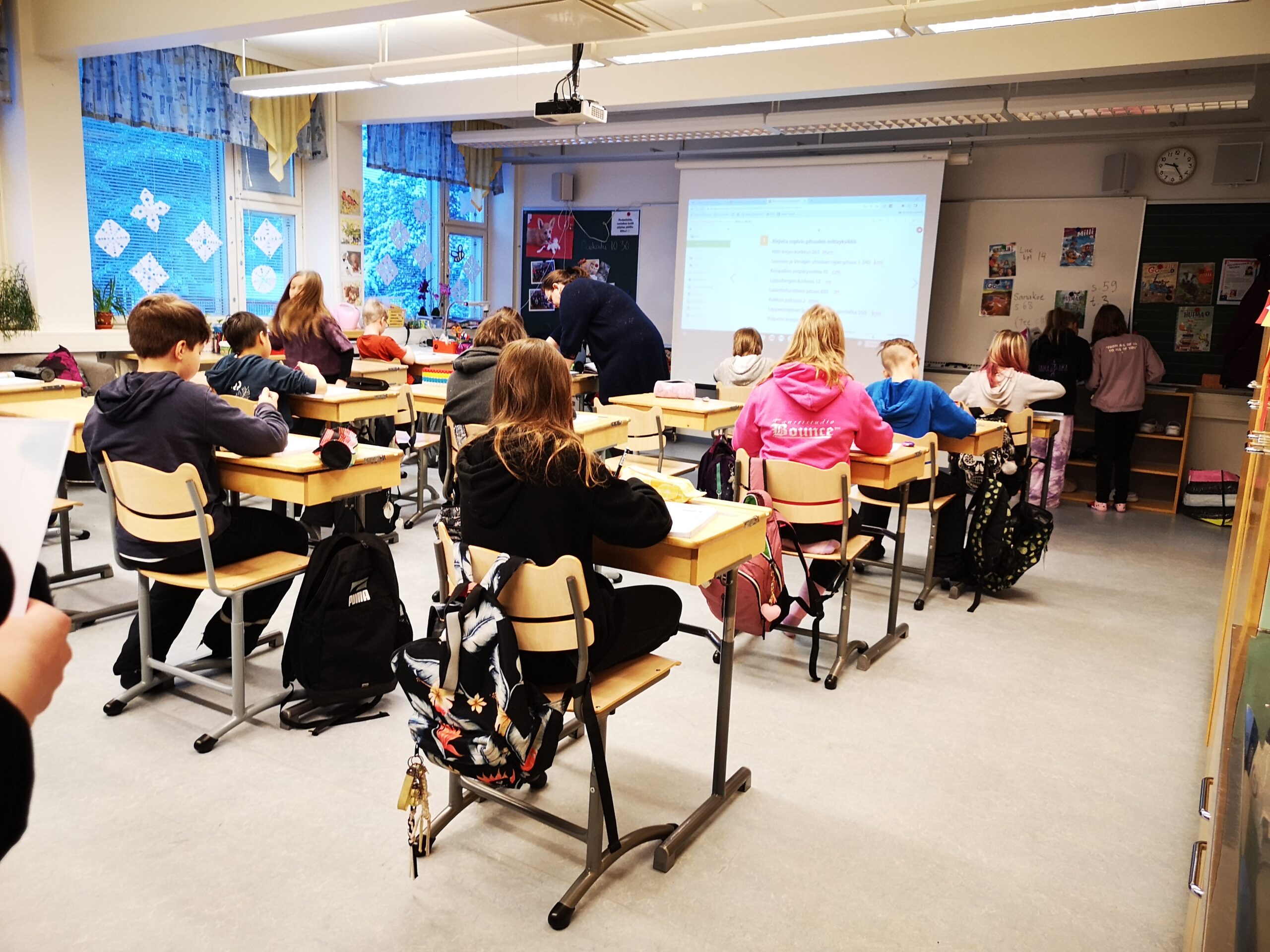

Learning environments are varied, encouraging pupils to explore their surroundings and form their own relationship with them. This supports a school culture that fosters growth and community.

Although recent international results show a slight decline, Finland continues to rank highly. Pupils report strong life satisfaction and low levels of school-related anxiety, reflecting the value placed on wellbeing.

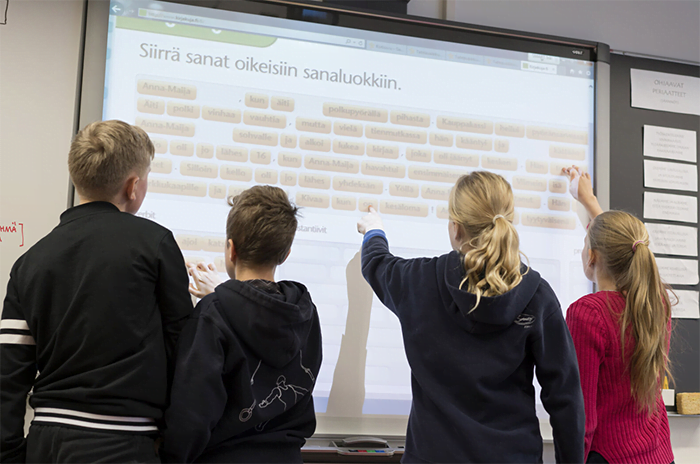

Transversal Competences

One key objective of the new curriculum is to increase integration and dialogue between subjects. Real-life phenomena are used as starting points for learning, and pupils are encouraged to combine knowledge and skills from different subjects in collaborative problem-solving situations.

To respond to future challenges, the curriculum focuses on transversal (generic) competences that cut across school subjects. These competences are:

- Built into every subject

- Promoted through multidisciplinary and cross-curricular work

Although the term “phenomenon-based learning” is not explicitly used in the core curriculum, integrating content and blurring the boundaries between subjects is a core feature. Working across subjects helps pupils understand complex phenomena and causal relationships.

Schools are required to organise at least one multidisciplinary learning module each year. In addition, teachers can plan thematic projects, parallel units or sequential learning paths that bring different subjects together. Teaching is understood more and more as holistic, integrated instruction, rather than separate subject blocks.

Room for Local Variation and Specificity

The national core curriculum sets a common standard across Finland, while allowing room for local adaptation. Municipalities design their own curricula, and schools create annual plans that translate national goals into everyday practice.

Teachers have wide pedagogical autonomy to choose methods that fit their pupils and local context—whether shaped by local industries, nature, community traditions or regional identity. All decisions must still follow the Basic Education Act and national curriculum.

Schools increasingly involve pupils in planning learning projects, from topics to working methods. This approach treats pupils as active partners and supports identity building through meaningful, locally relevant learning.

Collaboration Between Home and School

In Finland, schools and families work closely to support pupils’ wellbeing and learning. Communication is active and often handled through the Wilma application, where teachers and parents can exchange messages, track progress and address questions quickly.

Face-to-face contact remains important. Parents’ evenings, assessment discussions and everyday conversations help maintain trust and solve issues early.

Assessment – Focus on Learning, Not Testing

Assessment is continuous and designed to support learning. Teachers choose their own assessment methods—ranging from conversations and portfolios to self- and peer assessment—and share progress regularly with pupils and parents.

Younger pupils often receive written feedback rather than grades, while older pupils begin to receive numerical assessments. Assessment also guides teachers’ work, helping them adapt instruction and strengthen pupils’ ability to understand their own learning.

Finnish Teachers – Highly Trusted and Qualified Professionals

Teachers in Finland are highly educated and trusted to make professional decisions about teaching. Within the national curriculum framework, they select methods, materials and approaches that best support their pupils.

A Master’s degree is required for class teachers, subject teachers, special needs teachers and guidance counsellors, ensuring consistent quality across the country—whether in rural areas or larger cities.

School categories

Below you will find several categories of school visits. These visits form a key part of any study tour, and we strongly recommend including multiple visits to gain a well-rounded understanding of Finnish education. To deepen the experience, each tour should also include at least one expert lecture outlining the core features of the Finnish education system. With this background, the school visits become far more meaningful.

While lectures do increase the total cost, they are not more expensive than school visits. If the budget allows, adding cultural activities—such as welcome or farewell dinners—can further enrich the programme and offer a deeper insight into Finnish people and culture.